Women of the Nation Arise!

Staten Islanders in the Fight for Women’s Right to Vote

Acknowledgements ResourcesIntroduction

On View March 7, 2020 – June 20, 2021

Women in the United States won a long-fought national victory in 1920 when the 19th Constitutional Amendment establishing their right to vote was ratified. Women in New York had earned that right in a state referendum in 1917. Staten Island’s role in the fight for woman suffrage was both innovative on a national level and uniquely suited to the community from which it came.

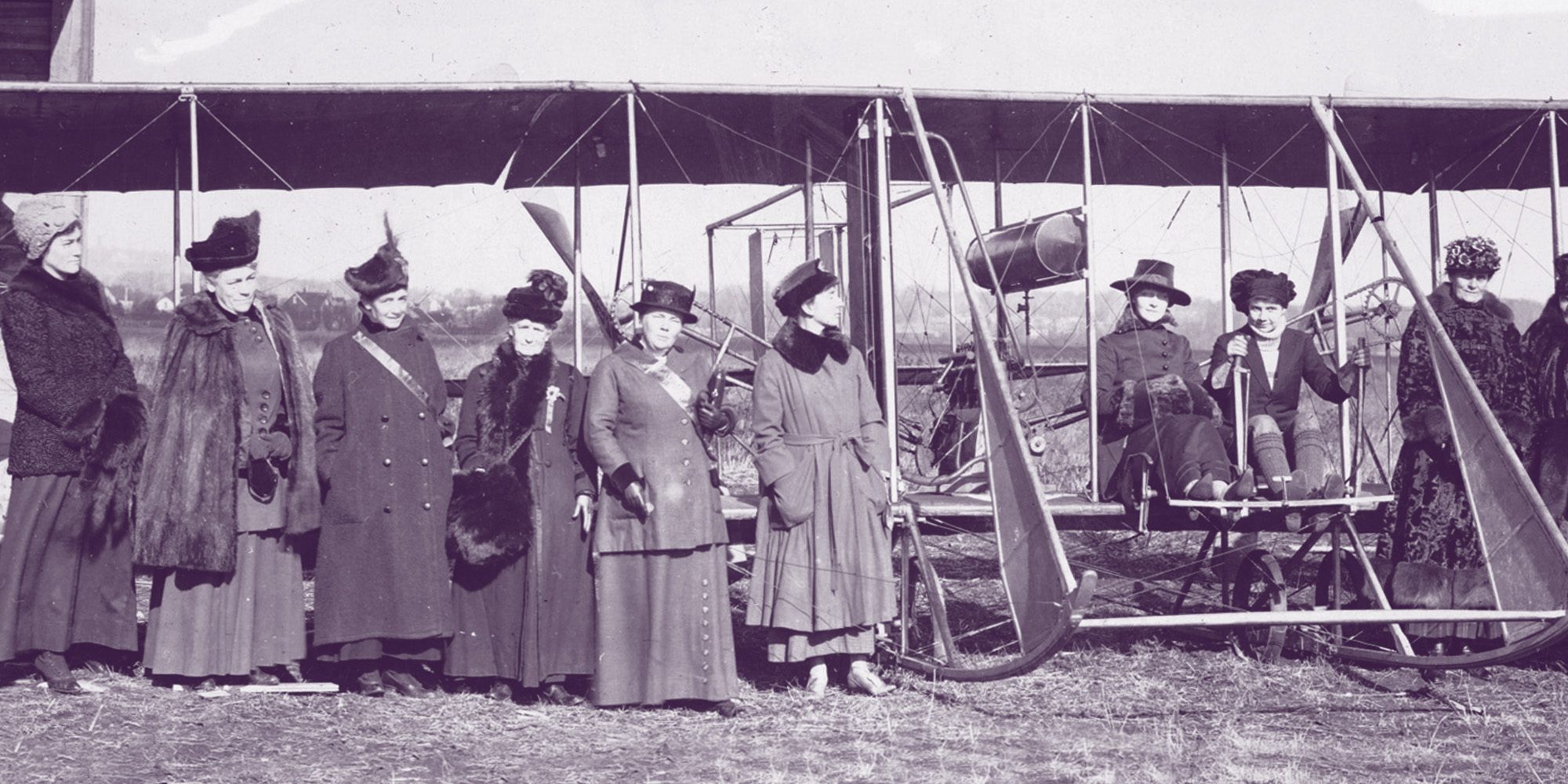

Women of the Nation Arise! presents stories of Staten Island suffragists focusing on four tactics they used in the decades-long struggle for political change before they could vote: education, organization, agitation, and publicity. As the site of the first flight for woman suffrage in the United States, Staten Island provided a distinctive setting for suffrage activism.

One hundred years later, this exhibition also critically examines the woman suffrage movement as a complex web of imperfect strategies. Suffragists often leveraged racial, economic, ethnic, and geographical biases to advance their cause. In doing so, the movement both divided and unified women in building consensus in their efforts to win the right to vote.

The ratification of the 19th Amendment was a major milestone in American Democracy. The law added millions of women to the rolls of American voters, but it did not secure voting rights for all citizens. Efforts to ensure and expand access to the polls continued beyond 1920 and to this day. We celebrate the achievements of local suffragists acting on the grassroots level to create the momentum necessary for regional and national change. Their steadfast perseverance to achieve self-determination set a new standard for civic responsibility that still astounds and challenges us today.

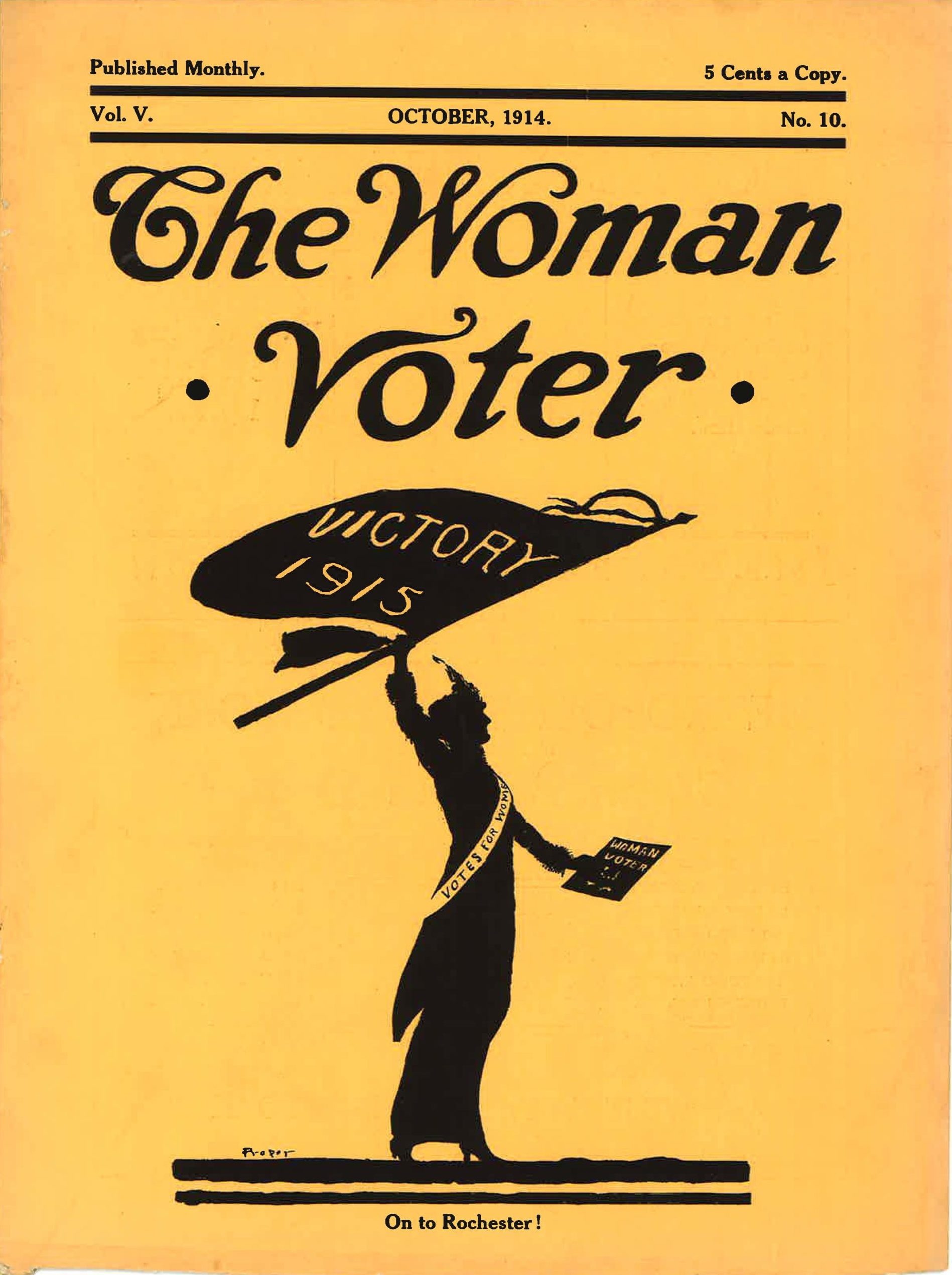

Collection of Staten Island Museum View Document

The right of the citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied by the United States or by any state on account of sex.

—19th Amendment

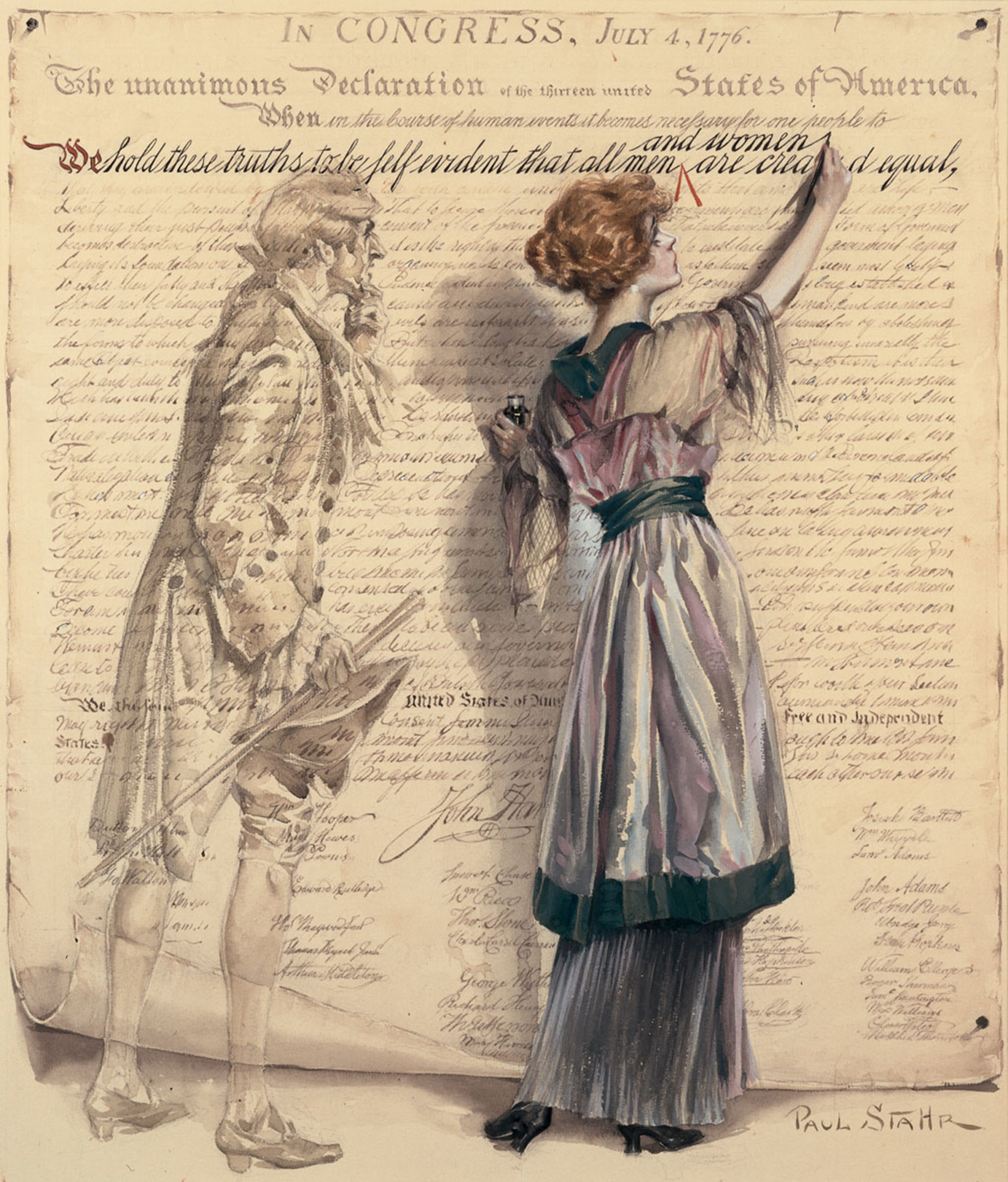

Life Cover illustration, July 1915 Paul Stahr (1882-1953) Courtesy of The Library of Congress | us0112

The Woman Suffrage Movement

The United States of America was founded on the principle of equal rights for all citizens; however, the original definition of citizenship was narrowly focused on wealthy male property owners. Throughout time, this definition has expanded and contracted to include and exclude people based on their race, class, gender, and ethnicity.

Women began to argue for their inclusion as citizens early in the nation’s history, drawing inspiration from its founders as well as the democratic and matriarchal traditions of Native American culture. In 1848, a group of New Yorkers that included Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Lucretia Mott, Jane Hunt, Mary Ann M’Clintock, and Martha Coffin Wright, organized the Seneca Falls Convention, the first formal women’s rights convention in the world. The venerable Frederick Douglass attended.

The Convention produced a document, modeled after the Declaration of Independence that declared, “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men and women are created equal.” Called the Declaration of Sentiments, it spelled out the rights that women lacked and demanded, such as the right of married women to own property independently of their husbands, to have custody of their children in the event of divorce, to speak in the church and in public, and to participate in government through voting. As they organized, suffragists strategically developed arguments to garner support from particular interest groups. Some argued that women are inherently moral beings whose votes would keep the country on course; others used anti-Black and anti-immigrant rhetoric to justify woman’s right vote. Despite this, women of color and immigrant women made their own space in the movement.

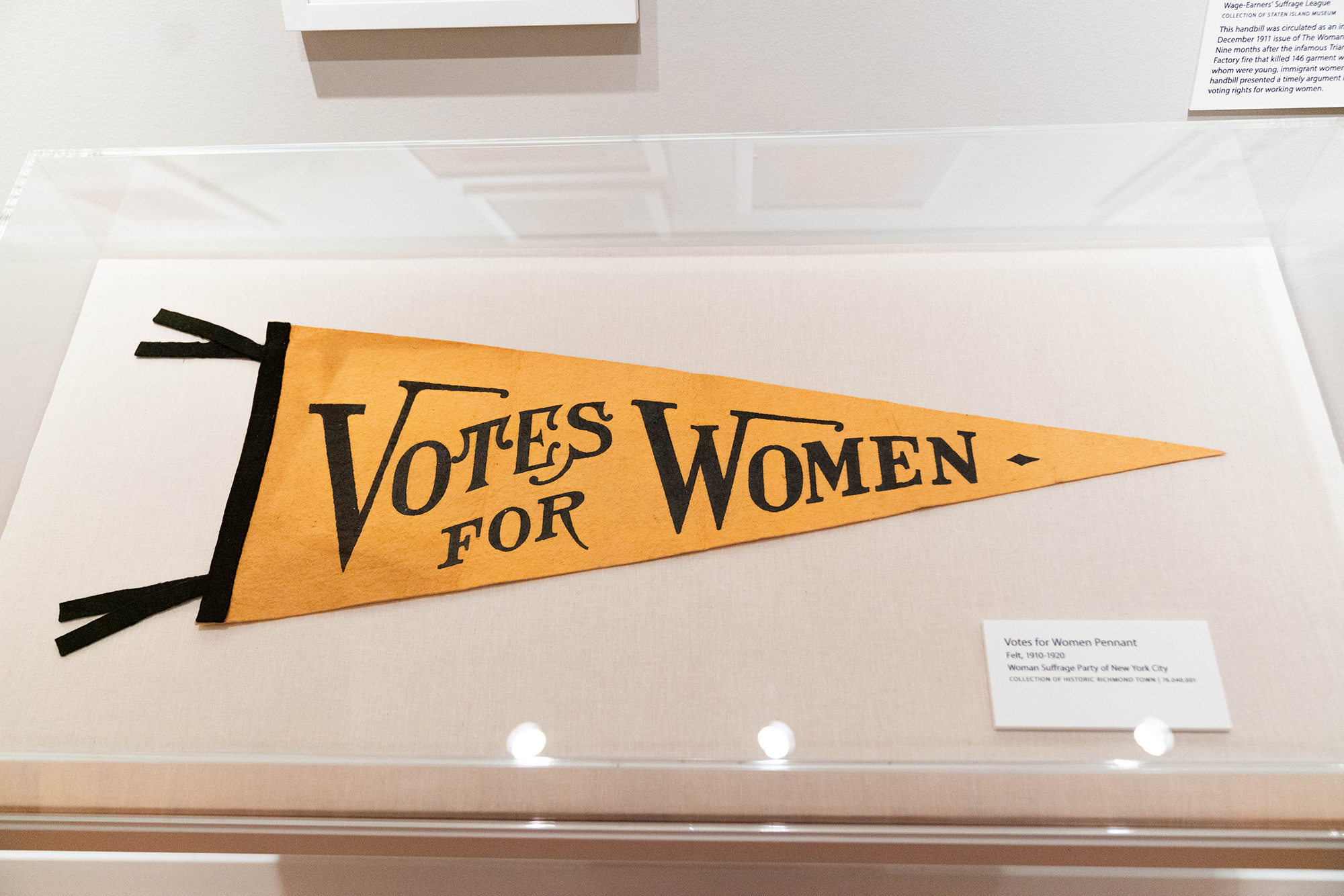

Felt, 1920-1920 Women Suffrage Party of New York City Collection of Historic Richmond Town