Women of the Nation Arise!

Staten Islanders in the Fight for Women’s Right to Vote

Acknowledgements ResourcesEducate

Suffragists had to educate both men and women that women’s views mattered and that they had a right to participate in government. Staten Island suffragists argued their cause before the houses of the New York State Legislature, to women gathered in parlors and clubs, and to male voters everywhere from lecture halls to street corners.

“We must bestir ourselves politically, morally, charitably and religiously, and help to bear the burdens which belong to true citizenship.”

– Mary Otis Willcox

Changing Norms

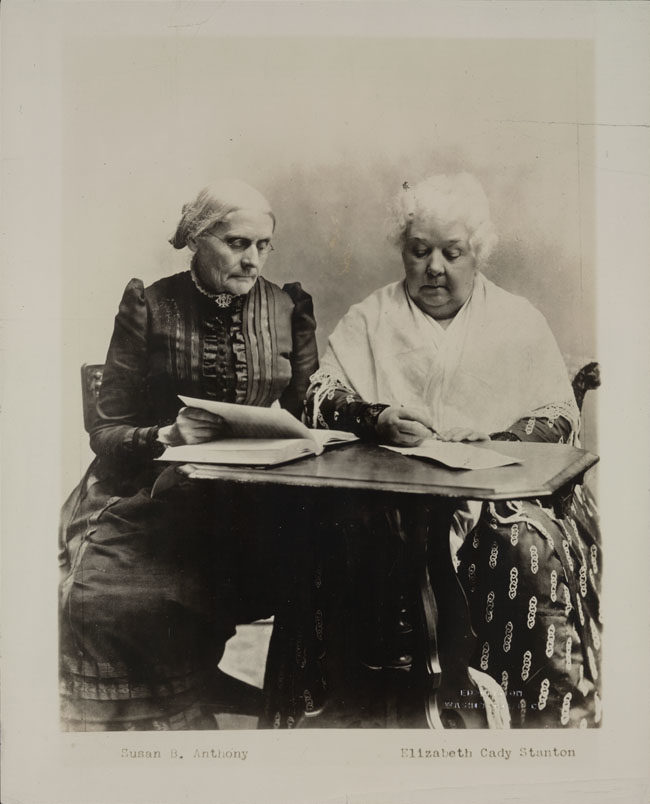

Women on Staten Island and all over the country were politically active long before they had the right to vote. They joined national leaders such as Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, and Frances Willard in movements advocating for the abolition of slavery and temperance in alcohol consumption. However, both laws and social norms kept women from participating fully in civic life.

Women’s exclusion from full citizenship was rooted in the idea that women and men should occupy “separate spheres.” According to this ideology, men should participate in public affairs like pursuing a profession or participating in politics, while women should focus on domestic matters, specifically raising their children to uphold these ideals. Few women ever conformed strictly to this idealized domestic role, and as more women gained greater access to education, joined political movements, and harnessed newly available technologies in the early twentieth century, they expanded their influence further into the public sphere. The women who participated in the suffrage movement and argued that women should be equal citizens with men justified the expansion of women’s roles by offering an ideology that directly undermined the idea of “separate spheres.”

Photograph, n.d. Collection of the Massachusetts Historical Society | 81.274

Elizabeth Neall Gay (1819 - 1907)

A Quaker from Pennsylvania, Elizabeth Neall was dedicated to ending slavery and accustomed to women’s equal participation in political discourse. However, when she attended the 1840 World Anti-Slavery Convention in London alongside early women’s rights leaders Lucretia Mott and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, women were barred from the proceedings. Suffragists later pointed to the meeting as a catalyst for organizing the women’s rights movement. A few years later, Neall married journalist Sydney Howard Gay, editor of the Anti-Slavery Standard and moved to Staten Island. The couple opened their home to freedom seekers on the Underground Railroad. Elizabeth remained committed to women’s rights, a conviction she passed on to her daughter Mary Otis (Gay) Willcox.

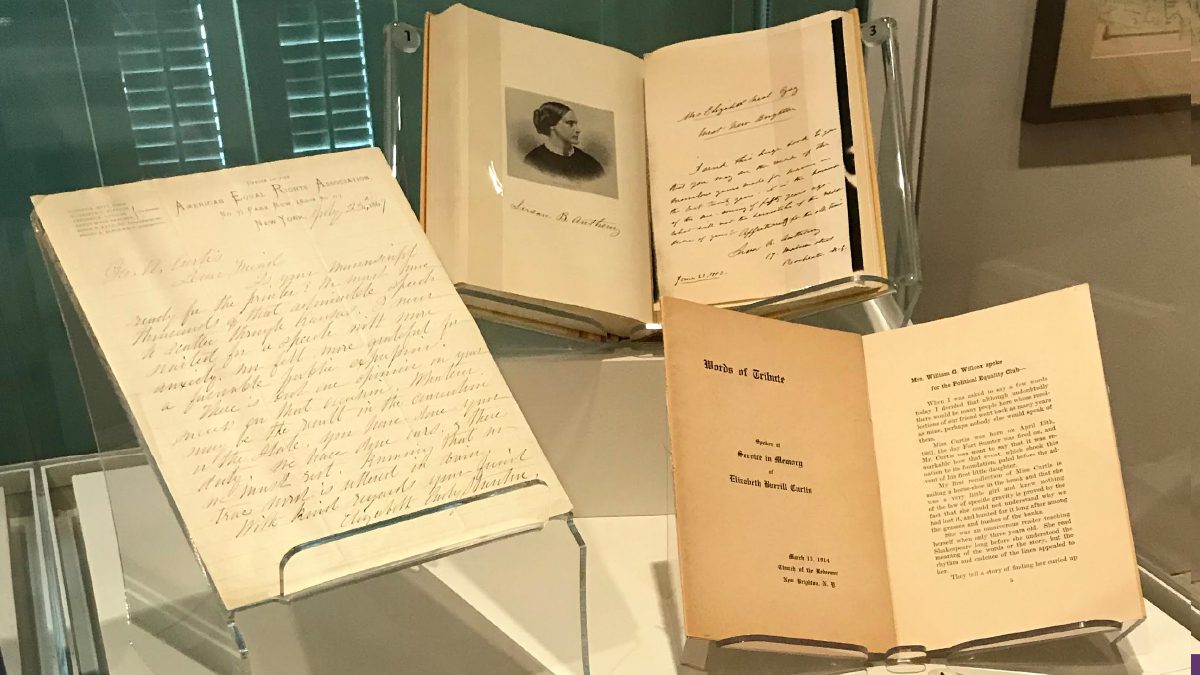

Left: Letter from Elizabeth Cady Stanton to George William Curtis (View the PDF) Middle: Susan B. Anthony's Inscription in Elizabeth Neall Gay's copy of "History of Woman Suffrage" (View the PDF) Right: Words of Tribute for Elizabeth Burrill Curtis (View the PDF)

Changing Laws

Staten Island women had two potential routes to the vote: Either the New York State Legislature would amend the state constitution to include women’s right to vote or the United States Congress would amend the Constitution to bar states from sex-based discrimination at the polls.

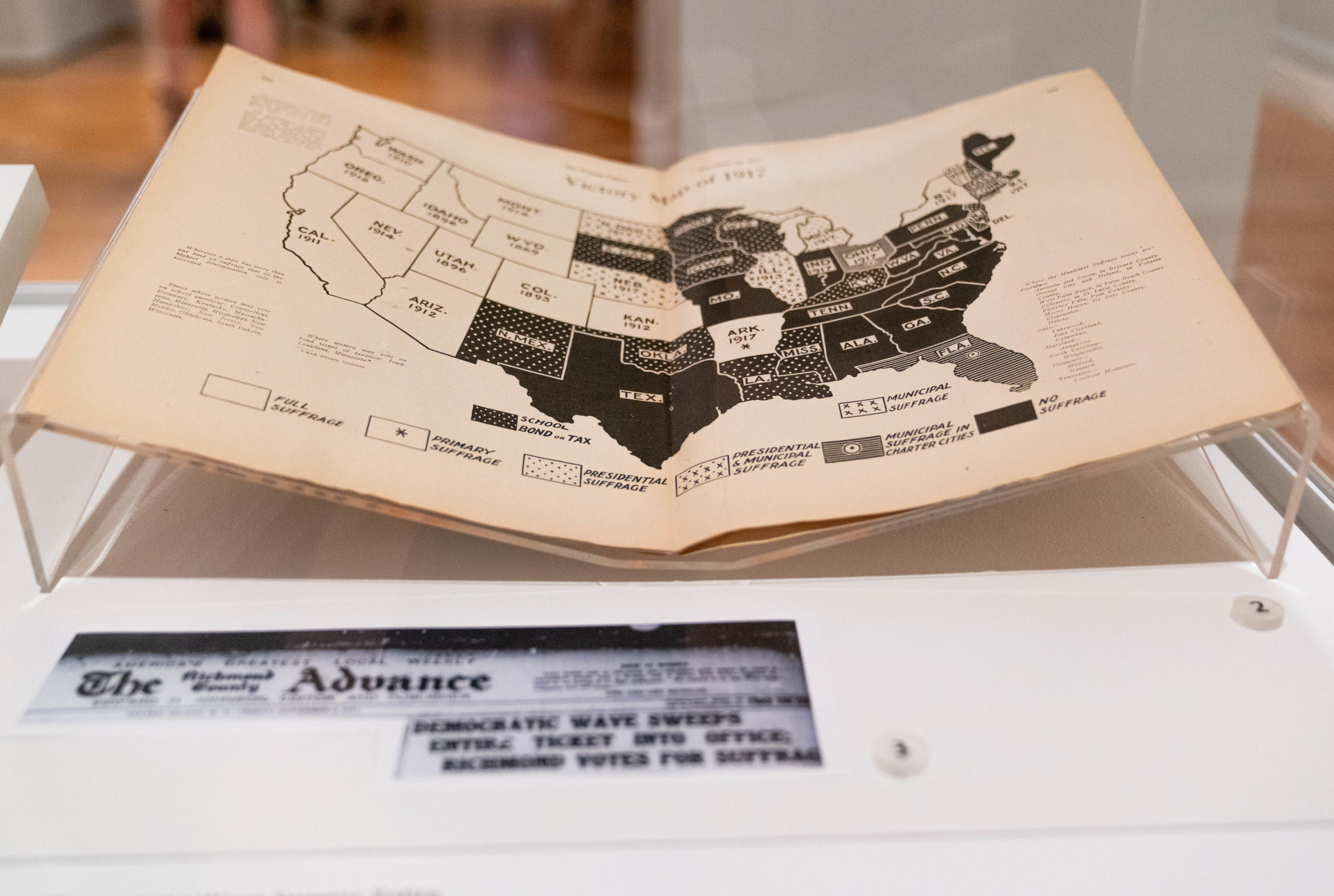

Nationally, suffragists disagreed over whether a state-by-state strategy or a federal strategy would be most effective. Staten Islanders were involved at all levels and during the entire suffrage campaign but gave special attention to changing New York State law during the Empire State Campaign, a roughly three-year effort focused on “Victory in 1915,” which ultimately fell short. However, on November 6, 1917, New Yorkers finally voted to amend the state constitution to include women as voters.

1915 wasn’t the first time New York’s suffragists experienced defeat in their struggle to vote. They had unsuccessfully lobbied for an amendment during several previous state constitutional conventions called to rewrite or change the state’s main governing document. Political dynamos George William Curtis and his daughter Elizabeth Burrill Curtis represented Staten Island at the conventions of 1867 and 1894 respectively.

Photograph, 1909 Collection of Staten Island Museum | K 6090

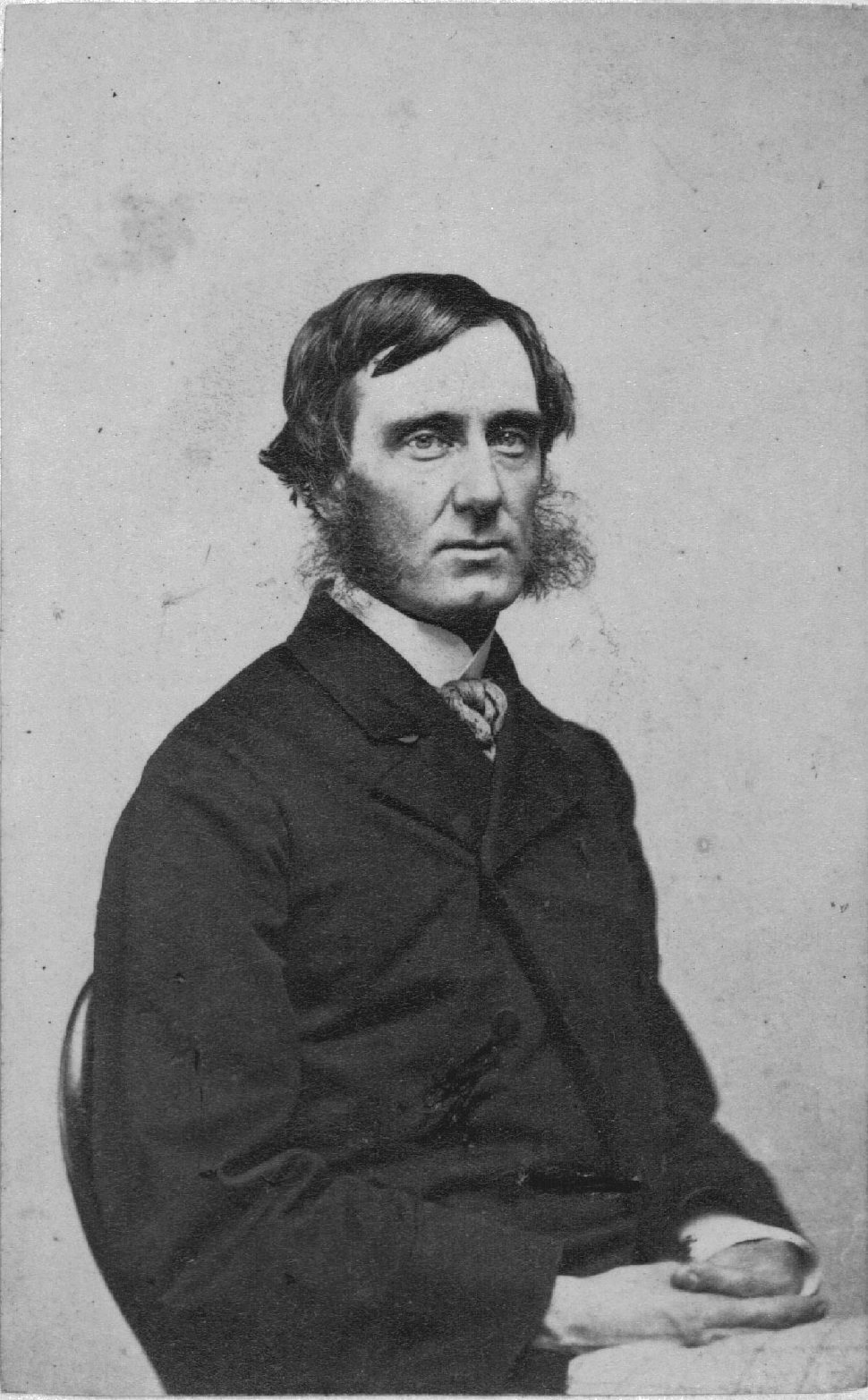

George William Curtis (1824 - 1893)

An internationally renowned orator, author, and editor, George William Curtis settled on Staten Island in the 1850s to marry Anna Shaw of the influential Shaw Family. He supported universal suffrage, the extension of voting rights to men and women regardless of race or color. In his speech at the 1867 New York State Constitutional Convention, he declared that “a woman has the same right to her life, liberty and property that a man has and she has consequently the same right to an equality of protection that he has,” earning the praise of his friend, suffrage leader Elizabeth Cady Stanton (Read the letter here).

Photograph, n.d. Collection of Staten Island Museum | 4183

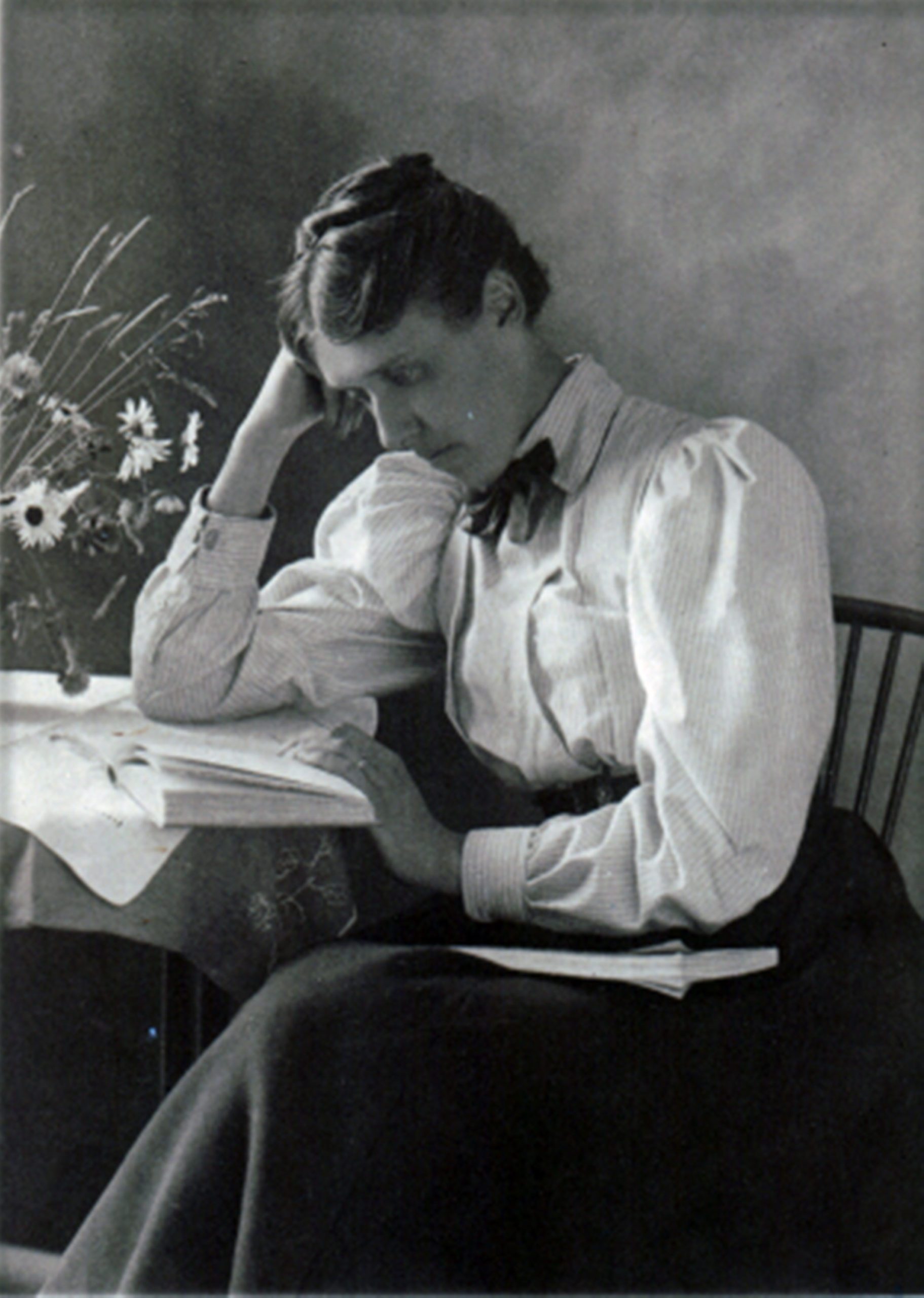

Elizabeth Burrill Curtis (1861 - 1914)

Elizabeth Burrill Curtis proudly carried on the progressive legacy of the Shaw and Curtis families as a vocal advocate for voting rights and civic education for women. At the 1894 New York State Constitutional Convention, Curtis argued, “Because the protection and safety of the home are so vital to most women…I plead for the power to effectually guard that home.” Her pleas went unanswered, but she was undeterred by the loss. Curtis founded the Political Equality Club, “the first organization on Staten Island to preach the equality of women and men,” in 1895. After her death in 1914, fellow suffragist Mary Otis Willcox said of Curtis’ contribution to the movement, “By the force of her personality [she] raised the cause from a subject of ridicule to one at least for serious consideration.”

Changing Strategies

The Political Equality Club conducted its earliest meetings as lectures and discussions in the parlors of West New Brighton’s social elite. Eventually, local suffragists expanded their tactics to include broader recruitment efforts like automobile tours and open-air meetings, seeking to unite women from the various towns on Staten Island in an active campaign for the vote. They drove guest speakers across the Island, pulling over and addressing passersby on the street. Their aims were to engage with voters, recruit women to the cause, and encourage women to talk about suffrage with the men in their lives since only men’s votes could secure woman suffrage.

The Women Voter, 1917 Gift of Arthur Hollick Collection of Staten Island Museum | A1919.1371

Mary Otis Willcox (1861 – 1933)

Described as “indefatigable” by her fellow suffragists, Willcox began her work as an officer in the Political Equality Club and then spearheaded the local campaign as Chair of the Staten Island Woman Suffrage Party. A wealthy woman, Willcox was able to host many of the Party’s events in her home, provide her car to transport suffrage speakers around the island, and give generously to the movement’s fundraising efforts. She and her husband, William G. Willcox supported many of Staten Island’s charitable organizations, including the Red Cross, Shiloh AME Zion Church, and the Staten Island Museum. In fact, at her death, the Museum recognized her as the first woman to serve on its Board of Trustees.

Click here to read an article by Mary Otis Willcox in The Woman Voter. Despite Willcox’s prediction, women in New York did not win the right to vote in 1915, but they would two years later in 1917.